Geographic atrophy

progression

Geographic atrophy progression is continuous and irreversible.1–4

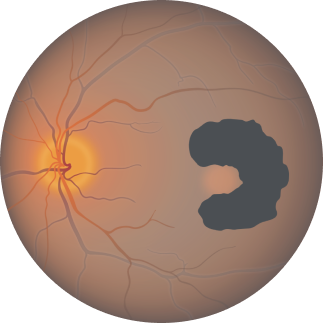

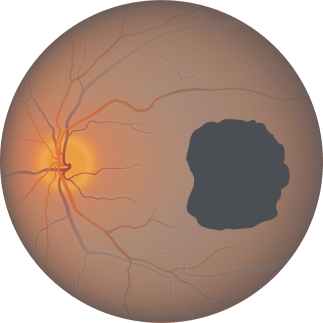

While lesion growth in geographic atrophy may appear to proceed slowly, disease progression is continuous and irreversible.

Growth of GA lesions lead to visual impairment, even before lesion growth reaches the fovea.

Of the 397 patients who developed central GA, the median time to foveal encroachment was only 2.5 years from diagnosis, according to a prospective AREDS study (N=3640).

Currently geographic atrophy affects more than 5 million people worldwide.1

From age 50, prevalence quadruples every 10 years.5

Geographic atrophy accounts for around 25% of all legal blindness attributed to AMD.6–8

An eye with geographic atrophy can also naturally develop wet AMD.9

of patients with wet AMD progressed to geographic atrophy over an average of 7.3 years of follow-up.10

Geographic atrophy is characterised by progressive and irreversible loss of the photoreceptors, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and underlying choriocapillaris.1,11

Regions of atrophy typically start outside the fovea and expand to involve the fovea, which – over time – leads to permanent loss of vision.11

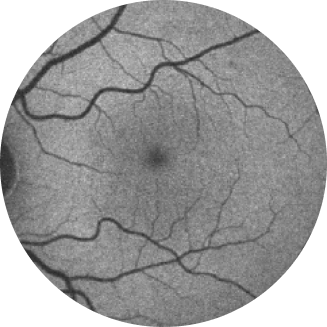

Fundus photograph of a healthy eye

Fundus photograph of an eye with geographic atrophy

Causes of geographic atrophy

Age-related macular degeneration is a complex, multifactorial disease and geographic atrophy pathogenesis encompasses a complex interaction of genetic, physiological and environmental factors.12–15

Genetics

- Drusen formation

- Formation of reactive oxygen species

- Inflammation

- Immune response, including complement

Physiology

- Age is the greatest risk factor for Geographic Atrophy

Environment

- Sunlight, smoking and diet

- High alcohol intake

Lesion growth may lead to visual decline.1,12,13

Visual acuity does not strongly correlate with geographic atrophy lesion growth. Functional vision declines as lesions grow.14

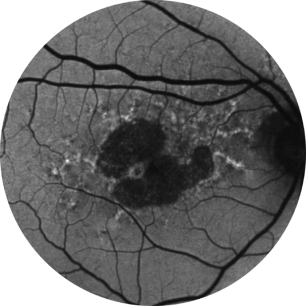

Baseline Year 1

BCVA 20/63+, GA Area 5.18 mm2

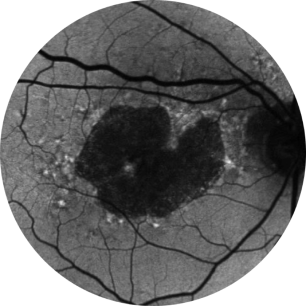

Baseline Year 2

BCVA 20/80-2, GA Area 10.39 mm2

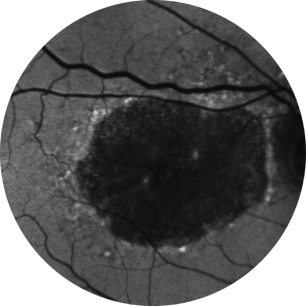

Baseline Year 5

BCVA 20/200, GA Area 18.58 mm2

Images courtesy of David Elchenbaum, MD, Retina Vitreous Associates of Florida.

BCVA = Best-corrected visual acuity.

Diagnosis of geographic atrophy

Retinal imaging techniques are used to identify, diagnose and monitor all stages of age-related macular degeneration, including geographic atrophy.15

When diagnosing and monitoring age-related macular degeneration an ophthalmologist, retinal specialist or optometrist will look for the following features in the retina:15

- Decorated with drusen

- A sharply demarcated area in the macular region with an atrophic retina, lacking pigmentation

- Visible underlying choroidal blood vessels

Normal fundus autofluorescence of a retina

Fundus autofluorescence angiography imaging is currently a standard imaging technology to visualise the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in geographic atrophy.16

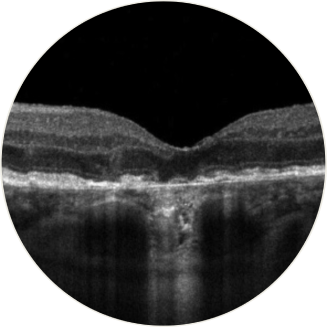

Horizontal OCT scan over the fovea

Optical coherence tomography (OCT): the atrophy of the retinal layers can be clearly seen with this non-invasive imaging technique.17

Current management approaches

Focus on coping with the disease, without slowing or stopping lesion growth.8,18,19

Visual rehab20

Low vision aids21

AREDS supplements22

Smoking cessation22

Exercise23

Diet22

AREDS = Age-Related Eye Disease Study.

AREDS supplements are not an approved therapy for GA.

Therapeutic approaches currently being investigated

To date, there are no approved therapies to reduce the rate of advanced dry AMD progression, although several potential therapies are under investigation.24-27

Discover the unmet need in geographic atrophy

Join us on our journey in geographic atrophy

Be the first to receive the latest geographic atrophy news

Thank you for submitting your details.

Please check your inbox for confirmation

References

- Boyer DS, et al. Retina. 2017;37(5):819–835.

- Lindblad AS, et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(9):1168–1174.

- Holz FG, et al. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(5):1079–1091.

- Sunness JS, et al. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(2):271–277.

- Rudnicka AR, et al. Ophthalmology. 2012; 119(3):571–580.

- Gehrs KM, et al. Ann Med. 2006;38(7):450–471.

- Biarnés M, et al. Optom Vis Sci. 2011;88(7):881–889.

- Chakravarthy U, et al. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(6): 842–849.

- BrightFocus Foundation. Age-related macular degeneration: Facts & figures. 2018. Available at: https://www.brightfocus.org/macular/article/age-related-macular-facts-figures (Accessed February 2024).

- Rofagha S, et al. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(11):pp.2292–2299.

- Fleckenstein M, et al. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(3):369–390.

- Kimel M, et al. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;57(14):6298–6304.

- Sadda S, et al. Retina. 2016;36(10):1806–1822.

- Heier JS, et al. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4(7):673–688.

- EyeWiki. Geographic Atrophy (n.d.). Available at: https://eyewiki.aao.org/Geographic_Atrophy (Accessed February 2024).

- Bearelly S, et al. Retina. 2011;31(1):81–6.

- Ferguson LR, et al. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e111203.

- Bandello F, et al. F1000Res. 2017;6:245.

- Sacconi R, et al. Ophthalmol Ther. 2017;6(1):69–77.

- Ramírez Estudillo JA, et al. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2017;3:21.

- Gopalakrishnan S, et al. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(5):886–889.

- Thorell M, Rosenfeld PJ. Curr Ophthalmol Rep. 2014;2(1):20–25.

- Seddon JM, et al. Arch Opthalmol. 2003;21(6):785–792.

- Buschini E, et al. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:563–574.

- Khanani AM, et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;232:49–57.

- Macular Society. Are we a step closer to treatming AMD with red light? Available at: https://www.macularsociety.org/about/media/news/2023/september/are-we-a-step-closer-to-treating-amd-with-red-light/ (Accessed February 2024).

- Ebeling MC, et al. Redox Biol. 2020;34:101552.

UK-GA-2300013 February 2024